The language of water – the language of the heart

20/10/2020

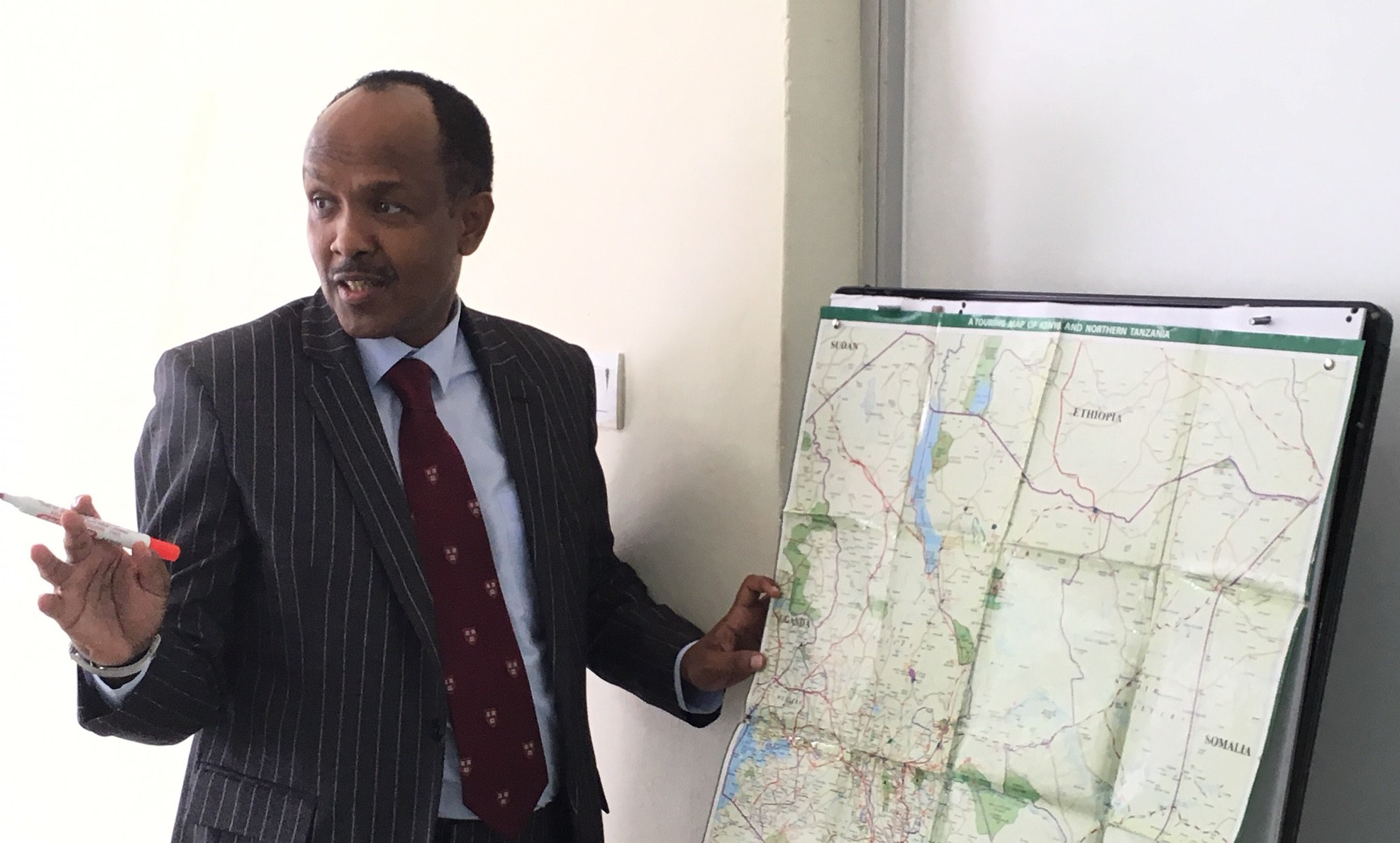

Habaswein, in Wajir County in northeastern Kenya, is arid and its inhabitants are poor. There is very little water for anything to grow. Mukhtar Ogle is a son of this land. He is also a Senior Advisor to the President of Kenya.

Far away in India, the Tarun Bharat Sangh (TBS) organization, led by Dr Rajendra Singh, has worked for decades to restore the watersheds of Rajasthan. Known as ‘the waterman of India’, Dr Singh has helped bring water to thousands of villages. The climate of this part of India and the climate of Habaswein are similar. What worked here could work in Kenya.

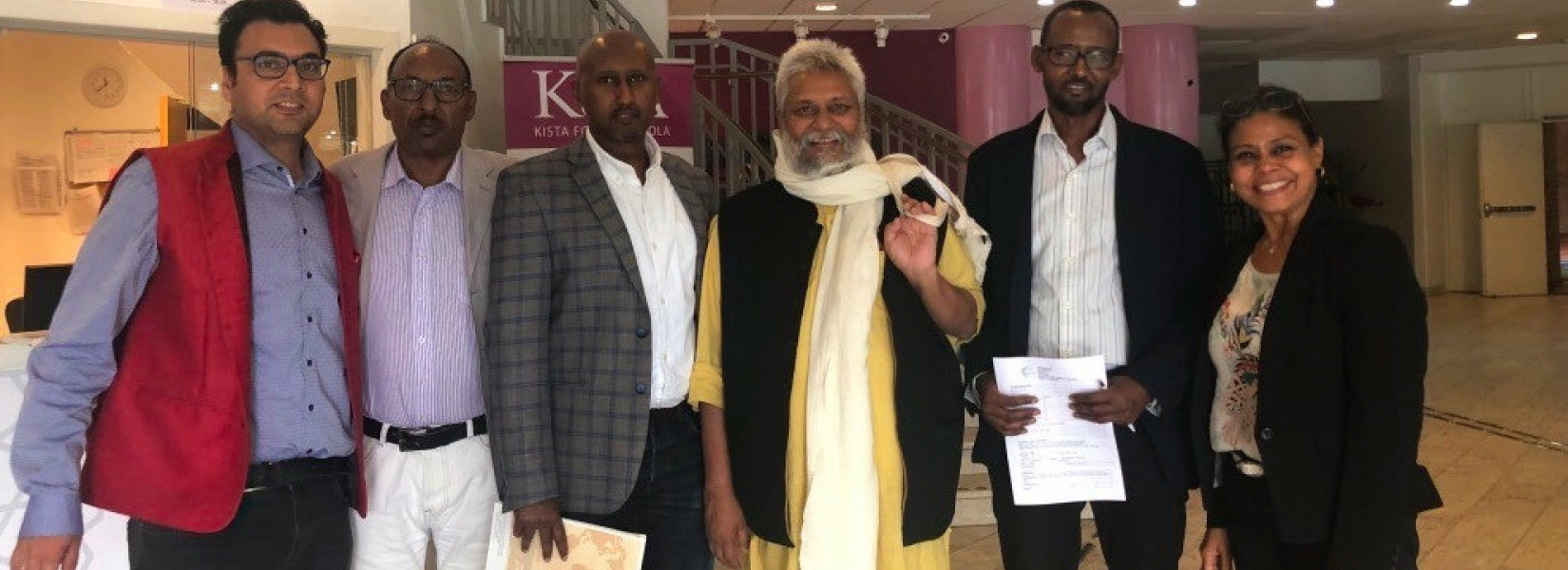

In August 2019, Dr Singh and Sunita Raut from Four Rooms of Change met with Rishabh Khanna and Hassan Mohmud from Initiatives for Land, Lives and Peace* (a programme of IofC International) in Sweden. A deep desire to bring water to the arid lands of the Horn of Africa connected them. They did not know how, but they had hope in their hearts and, more importantly, determination.

In February 2020, Mukhtar Ogle gave a keynote speech on environment and security at Asia Plateau, the IofC conference centre in India. He also visited Grampari, a rural development NGO inspired by IofC, which has done pioneering work in watershed management. And he heard more about Dr Singh. ‘Bring this to Kenya,’ said Ogle, ‘and we will transform the region.’

Rishabh Khanna, Sunita Raut and Hassan Mohmud were ready to deliver Dr Singh’s land and life-restoring methodology to northeastern Kenya. But as Covid-19 spread, their prospects of engaging with a remote town in northeastern Kenya seemed dashed.

That’s when Khanna and Raut initiated a Whatsapp group, linking Dr Singh with Mukhtar Ogle. After some calls, they decided to created an online training module in English based on online sessions in Hindi from TBS. Khanna and Raut devoted their spare time to the project – and the Water Warriors training programme came to birth.

Meanwhile Ogle spoke with the community in Habaswein, nominated Abdi Ahmed to be their spokesman and told them that they would get participatory online training from Sweden.

And so, in August 2020, the first online Water Warriors Training for the Somali-speaking community of Habaswein was conducted by three trainers sitting on a sofa in Stockholm, frequently joined by Mukhtar Ogle at his desk in the Executive Offices of the President in Nairobi.

The first three days of the programme taught the basic principles of watershed management with aspects of geological, hydrological and agricultural science and community building. Then came the half-day Water Lab, where they examined videos and photographs of the vegetable plots near Habaswein’s seasonal river. They compared what they were seeing with Google Earth maps of the terrain and did an online community mapping exercise of the watershed.

Raut and Khanna also facilitated a module on how to release inner blockages and to harness the flow of life, both within oneself and in relation to others. Strengthening trust and collaboration in the wider community is a vital part of the programme.

This was perhaps one of the first interventions of its kind involving both the head and the heart, and overcoming geographical and language boundaries. Technology has given a new meaning to ‘field visits’.

The Water Warriors’ vision is that before the next rains, the community in Habaswein will construct check dams and johads (percolation ponds), to hold back rainwater and start recharging the aquifers. The programme facilitators will accompany the community online throughout.

Now, the mission is to find partners and resources so we can deliver the three-part Water Warriors Training and the half-day Water Action Lab to more and more communities which dream of seeing water all year round.

*Initiatives for Land, Lives and Peace organizes the annual Caux Dialogue on Environment and Security (CDES) and co-organizes, in partnership with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, an annual Summer Academy on Land, Security and Climate. Mukhtar Ogle was on the faculty of the Summer Academy and a keynote speaker at CDES in 2019.

For further information, please contact:

- Rishabh Khanna – rishabh.khanna@iofc.org

- Sunita Raut – sunita.raut@fourrooms.com

Photo top showing: Dr Rajendra Singh (centre) with the Water Warriors facilitators in Sweden.

Photo credits: Water Warriors

Survey: How can we serve you best?

12/10/2020

We are committed to inspire, equip and connect you to support you on your journey from personal to global change. But we need your help to see how we can do this best!

This year, we had to learn how to organize and facilitate online events in order to bring Caux to you. It wasn't easy, but we were happy to be able to connect with so many of you who wouldn't have been able to come to Caux otherwise! As a lot of change is happening, we are taking this opportunity to reflect on what we offer and how.

To be able to serve you best, we would like to know more about your needs and desires. Please click here and fill in this survey before 20 October. The survey is short and will take you only a couple of minutes to complete!

Thank you in advance and stay tuned as you will hear about our upcoming events soon!

Lebanon deserves better

Caux Peace and Leadership Program (CPLP)

01/10/2020

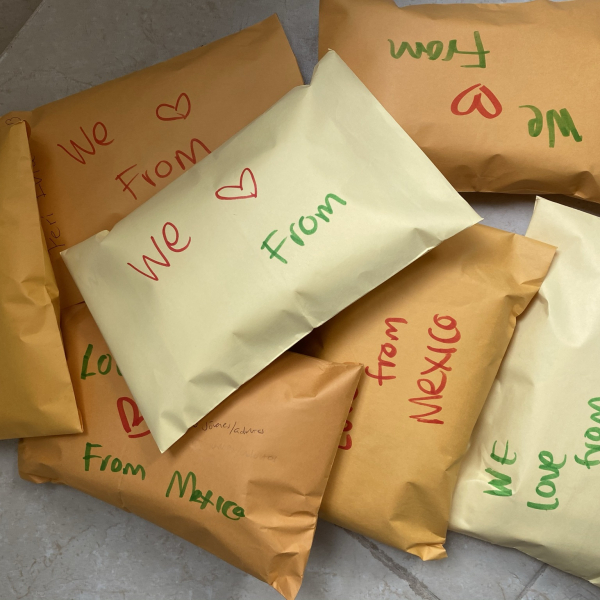

On 4 August 2020, the world was shocked to learn of the explosion which had torn through Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, claiming lives and property. Messages of love were sent to the people of Lebanon from all over the world.

The Caux Peace and Leadership Programme (CPLP) has a strong alumni presence in Lebanon. One of them, Sarah Taleb (ST), was in Beirut at the time of the explosion. She is a producing director, project manager and grant writer who specializes in cultural management. She took part in a virtual discussion with a representative interviewer (RI) from the CPLP.

RI: As difficult as it is, would you be happy to share with us your initial experience in the aftermath of the explosion in Beirut?

ST: My friend and I went to sleep elsewhere that night: our home was damaged and we didn’t want to stay there. I was numb for days, all of us were numb. I had to be there for my friend, even though I was still in denial. I kept saying: ‘No, this did not happen’. I felt it was the beginning of the end. I felt sad, and I stood with this sadness, refusing to be lifted up.

The thing that made this explosion different from others in the past wasn’t just how big it was, but what it took with it: a whole city. It was as if our collective memory had just been wiped out. People’s homes reduced to point blank, lives shattered along with the glass. Everyone knew someone who had died or been injured. A couple of days after the blast, we started cleaning houses of the rubble, dirt and shattered glass.

To this day, every time a door slams or when we hear a loud sound, we all jump. Our thoughts take us back to 4 August, when the clocks in Beirut stopped, literally, at around 6:00 pm.

RI: What was your initial reaction, and that of the people in Beirut?

ST: Everyone was angry. I was angry. The protests were built around our anger and frustration that our corrupt government could leave that amount of ammonium nitrate unsupervised and cause us to lose lives, homes and our city. During the protests, the army kept throwing tear gas at us: hundreds of people were injured every day.

For three days, I was personally angry at Lebanon. I insulted soldiers while driving, the parking lot concierge because he wouldn’t let me park in my spot, and two men for just looking at me the wrong way. I got to a point where I knew that I needed to walk away from those feelings of anger: my friends and family were worried I might end up in prison for it! I got hung up on my PlayStation for days, playing a video game and shooting at the soldiers. I guess that helped too.

RI: I have seen your Facebook feed and it shows that you have recently been painting houses?

ST: I felt I needed to be on the ground. We needed to do this to be able to move forward. It was not about inspiration, but about need. We all saw a huge need and we had to respond to it in one way or another. All Lebanese people found themselves contributing to rebuilding their neighborhoods, helping their injured neighbours or donating. I was painting houses. It gave me a chance to sit together with affected families, share a meal or a beer together and simply talk. It created a fun environment, built new memories – which is what a home is about, more than just bricks, paint and some utensils in the kitchen.

RI: That is powerful. What are your feelings about Beirut and Lebanon three weeks after the explosion?

ST: The pain will never go away. The mere fact of existing in Lebanon has become painful. Lebanon deserves better. But meeting families, helping people and knowing that these people care for you and love you genuinely, and vice versa, eases that pain. That’s the reason I’m able to stay here for a few months to come. I also chose to paint homes because it’s a thing I love to do. I find it’s a bonding activity, a symbolic act in itself. I have to admit that if I had not worked so much on my own personal growth, I would never have been strong enough to see people in their pain and suffering, and feel ready to serve and empathize with them.

If you want to be part of an online follow-up conversation with the CPLP alumni on Saturday, 10 October 2020 at 14:00 CEST, you can sign up through this link. You will find the terms and conditions here.

Find out more about the Caux Peace and Leadership Talks here.

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

Beyond the Rubble: the unseen impact of the Beirut explosion

Caux Peace and Leadership Program (CPLP)

21/09/2020

The Caux Peace and Leadership Programme is a programme of IofC Switzerland. Its alumni from over 40 countries want to make a change in their communities as well as themselves.

As part of the widening outreach of the programme, we are launching a new and thought-provoking series of articles and events which will allow our alumni to share their stories, experiences, challenges and how they have carried what they learnt at CPLP into their daily lives. Each month we will post a new article, offering you inspiration and food for thought and soul-searching. After each article, you can register to discuss the issues in more depth in an on-line follow-up conversation.

The series will start with our friends in Beirut, who have shown immense courage and strength following the devastating events of 4 August 2020. This will be in two parts starting today.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

When a home is a crime scene, you want to fly away, but that makes you want to hold on to it even more.

Antoine Chelala is a young graduate of the American University of Beirut, with a background in business and social psychology. He attended the Caux Peace and Leadership Programme in 2017 and 2019 and was involved in the inaugural Creative Leadership Conference in 2020, which coincided with the first-ever Caux Forum Online. Like many others, he was in Beirut on 4 August 2020, when a massive explosion occurred. This is his story.

I have always had a love-hate relationship with my country and the recent disaster in Beirut has reinforded these contradictory feelings.

Lebanon is home and I love home. There is no other place like it, even when it brings too much pain and sadness. When a home is being killed, destroyed and stolen from you, it is hard to feel safe. When a home is a crime scene, you want to fly away, but that makes you want to hold on to it even more. When justice seems to be unattainable, home will never be peaceful.

The blast that happened at the port of Beirut on 4 August 2020 at 6:07 pm will remain a horror in the hearts of all Lebanese people for ever. On this day, time stopped. A few seconds were enough to change everything. We were all bleeding in one way or another.

The week afterwards seemed to be the longest week of my life. I couldn’t pick up a pen. I will never find the right words to express what our eyes witnessed and what our hearts felt. I keep seeing the images in my head. I keep hearing the sounds. I keep reliving the moment and fearing that it will happen again.

How do I mourn a city? How do I mourn places? Memories? How do I mourn people I never met? Victims I will never know? How do I mourn cultural heritage sites? History and buildings? How do I mourn Beirut?

I have noticed that many people are writing to Beirut. I figured that, just maybe, addressing Beirut as a person might make it easier to cry over a dead city. Beirut, do you still dare to dream after what happened? Are you even listening when we tell you that you will rise again? Can your pain be covered by a layer of hope that we fiercely hold on to? Do you still feel proud when people call you the phoenix? No matter how much I write about you, the ink flowing from my pen will never be able to depict the flowing blood nor the flowing tears. I just need to admit that I will never find the words.

Somehow, I want to hold on to sadness. I want to stay in the stage of grieving because I feel responsible for keeping Beirut’s memory alive. I don’t want to let go too soon. I don’t want Beirut to sink into oblivion. All this pain cannot go away: I want to be moved by it every single day. All this suffering needs to be acknowledged and recognized.

I, and many people around me, feel guilty for not suffering enough. This feeling stands in the way of happiness, inner peace and mental clarity. Everyday activities such as reading a book, taking a walk or watching a movie suddenly became a luxury that only some of us can do. I don’t feel like I deserve these things while Beirut is still in ruins. Too many hearts are shattered, and unlike broken glass, no broom can sweep up these eternal scars. I also feel guilty because I know that, one day, things will go back to normal for me, since we have not lost any close family members, we are all well physically and our house still exists. Hundreds of thousands of other people will not be able to ‘go back to normal’, their lives are changed forever.

If you wish to be part of an online follow-up conversation with the CPLP alumni on Saturday, 10 October 2020 at 14:00 pm CEST, you can sign up through this link. You will find the terms and conditions here.

Find out more about the Caux Peace and Leadership Talks here.

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

- Learn more about the Caux Peace and Leadership Programme.

- Find out more about the Caux Forum.

- Discover Creative Leadership 2020.

Mohammed Abu-Nimer: Dialogue – Weaving peace into the fabric of society

Tools for Changemakers 2020

19/09/2020

Mohammed Abu-Nimer is Professor at the American University’s School of International Service in International Peace and Conflict Resolution in Washington DC and a Senior Advisor to the International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID). He is an expert on conflict resolution and has been facilitating dialogues for 30 years. He has been one of the main faculty of the Caux Scholars Program since 1993 and was a speaker at Tools for Changemakers in July 2020. He agreed to tell us more about the role dialogue plays in building sustainable peace.

Peace-building runs in Professor Abu-Nimer’s blood: for many years his grandfather was a mediator in his community. He experienced his first dialogue at the age of 19 when he started university. At that time he thought dialogue was a form of political activism. He discovered that while political activism and dialogue both aim at change, dialogue does it by building relationships, enhancing our understanding of ourselves and others, and finding common ways to bring that change, rather than through confrontation, blame or shame. Since then, he has been applying dialogue to resolving interfaith, interethnic and interracial conflicts all over the world.

What is dialogue?

Dialogue, he says, starts with finding commonalities with others that enable us to see them as humans and build a relationship with them. However, he insists, this is not the most important step. The next, and more difficult, step is to explore the differences. ‘We use our commonalities to construct a web of relationships that allow people to solve their challenges and differences peacefully,’ he says. ‘But it’s not only relating to the other, it’s answering the question of what we can we do together to address the issues.’ Dialogue has the power to develop concrete strategies to bring peace in the community.

No justice, no peace

Peace is impossible without justice, Abu-Nimer continues. ‘For African American and non-white people in the United States, for example, there can be no full reconciliation with the dominant political system, and with the community that supports it, without structural changes.’ Dialogue can contribute to structural change by making its participants ‘realize that there are many ways to get to justice, including political activism, boycott and all the other techniques of peace and non-violent resistance’.

Although dialogue is not the only gate to peace, it makes peace sustainable. Structural change alone is often not sufficient. In South Africa, for instance, the abolition of apartheid led to a huge shift in the system, but this didn’t stop racial segregation, cultural violence and racial biases. ‘You can have a structure that is fair and just, but if that’s not accompanied with dialogue and with a culture and practices of peace, there is no guarantee that peace will be sustained. If anything happens (such as a natural disaster or increased economic hardship), people may revert back to violent conflict.’ Dialogue promotes a deeper kind of peace because it builds peace at the individual level. ‘Dialogue is the most powerful tool for the prevention of violent conflict. You will always have conflict, but dialogue can prevent the violence of it.’

Fostering a culture of dialogue

The International Dialogue Centre (KAICIID), where Abu-Nimer is a Senior Advisor, aims at building a culture of peace. He wants dialogue to become part of the curriculum, taught to children as an essential skill, like crossing the road safely. Everyone needs to ‘master some of the basic tools of dialogue’ if we are to create a society that is less cruel, racist and xenophobic. In a society where we were all well-versed in dialogue, we would give other people the chance to say what they want without judging them and labeling them. ‘If we don’t institutionalize dialogue, much of our efforts to build peace will be lagging.’

Through dialogue, we not only encounter others, but also ourselves, says Abu-Nimer. ‘Dialogue deepens our understanding of ourselves, of what we want and what is important for us. This changes us and makes us grow as humans. Dialogue has helped me to be more patient, to appreciate everyone’s perspective and to avoid as much as possible judging other people. It also allows me to hear the grievances of others in a clearer way and enables me to understand myself better.’ By practising dialogue, we become more aware of how limited our awareness of the world is and how we depend on other people to achieve what we want.

Where to start?

He provides two final pieces of advice for anyone who finds themselves involved in a conflict, whatever it may be. First: ‘Ask yourself what your role in the conflict is and become aware of it.’ Second: ‘Understand that a conflict is an opportunity for change. It is an attempt to deal with relationships of dependency and interdependency.’ Identifying what the other party wants and ‘how you can help them get what they want without losing yourself and what you want’ will help you find a way to solve the conflict peacefully and to grow.

Read more on Tools for Changemakers 2020

Learning to be a Peacemaker 2020

By Sabica Pardesi

12/08/2020

Sabica Pardesi is 24 years old and participated at this year's online version of Learning to be a Peacemaker. She is currently pursuing her Masters in Digital Business with a background in Fine Arts. Her research focuses on high-growth digital startups in South Africa and digital marketing. She is passionate about social impact through creative and entrepreneurial initiatives.

"I am really thankful to the person who introduced me to the Initiatives for Change programme Learning to be a Peacemaker. It was life-changing in so many ways. It opened my eyes to things we know in theory, but don’t really put into practice either actively or consciously. So, here are some of my thoughts on the programme and why I enjoyed it so much.

From the outset, I found myself in a safe bubble with a wonderful group of keen learners. I had expected to attend a lecture, but instead found myself taking part in a dialogue with stories. Together we discussed and unpacked the “why” of peacemaking.

It was a unique experience where people from different backgrounds, cultures and journeys came together to understand what peace means. Growing up in a Muslim home, we all know the basics of Islamic teachings, the pillars, and the qualities of human attributes. Yet, we practice what fits, what is contextually appropriate and what meets our terms. In a few days we unpacked Islam as a means of preserving life. We started from the core principles of Islamic and Quranic teachings, the struggles, the life of the Prophet, perspectives on loyalty and global citizenship, finally building up to the qualities of a peacemaker, all intertwined with stories, and relevant examples.

Islam means peace. This is not something that can be worn like a blanket when we feel the need for warmth, but something that needs to be processed, internalised and submitted to. Then, the warmth will come from within. We will no longer feel the need to be accepted, to be heard, to be followed. We will find that everything will be enough. We cannot be peacemakers without first ‘uncapping’ this inner peace. Anyone can uncap their inner peace by accepting the higher power. In Islam when we submit to the oneness of God, we acknowledge that He is all knowing and all seeing. Knowing that I am never alone feels like a big warm hug. His presence is eternal and that gives rise to the practice of awareness. That is right, it is something that is practised and developed overtime. To become more aware, we must be conscious of our every intention, action and utterance.

Before this course, I was another person looking to change the world and spread peace. As young people, we carry the anger and pain passed onto us by our parents, by our nations and cultural biases. We are quick to voice injustices and make statements. Although this is not wrong, we often fail to account for sustainability. The course really made me ponder how we do good for the short-term, we treat the symptoms and not the cause. This stems from a lack of knowledge and the pursuit of quick wins. We live in a world where we are continuously seeking to differentiate ourselves, to become better than one another. But a peaceful society comes from merely accepting our differences and embracing one another.

Now that the course is over I am still someone who wants to change the world, but I now know that peace does not just have to be spread, it needs to be cultivated and nurtured. For this I need to practice awareness, as well as the qualities of peacemaking. I also need to acquire knowledge and be patient. My generation which feeds on instant gratification for a living is in for a mighty challenge. But perhaps future generations will reap the benefits.

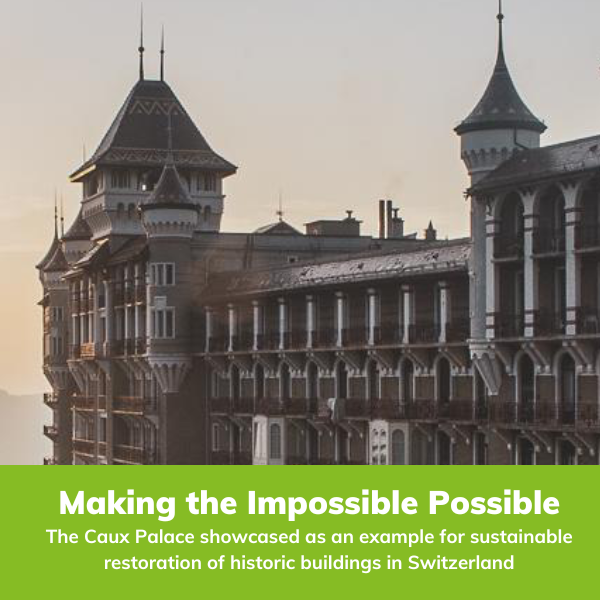

Swiss National Day in the gardens of the Caux Palace

1 August 2020

05/08/2020

Usually, Swiss National Day on 1 August is an opportunity for Caux Forum participants to discover some Swiss traditions, including cheese fondue. This year, it looked like the Caux Palace would be empty, and most celebrations in the area were cancelled. However, the large terrace of the Caux Palace was a perfect place to throw a party where locals could celebrate at a safe distance from each other. IofC Switzerland partnered with the Society for the Development of Caux and L’Artisan Glacier to offer a festive programme.

During the warm summer day, more than 300 people came at different times to enjoy the beautiful view and the entertaining programme. Following Swiss tradition, the day opened with a concert of alp horns in the gardens. Delicious food prepared by our dedicated team was available all day long, as was the bouncy castle for younger visitors. In the afternoon, we offered discovery tours of the Caux Palace in three languages. Most were fully booked, showing how eager locals are to learn more about this magnificent Belle Epoque building and its rich history. In the late afternoon, the Lounge Band jazzed up the party that went on through the evening.

We would like to thank all those who visited us on this Swiss National Day and look forward to other opportunities to celebrate in the Caux Palace gardens.

Tools for Changemakers 2020 – Shaping the future together through dialogue

17 - 19 July 2020

29/07/2020

Can you truly listen? What if we all had the power to make our communities more cohesive and inclusive by starting to deeply listen to each other? The Tools for Changemakers conference was a three-day experiential journey designed to equip participants with the powerful tool of dialogue. More than 180 active or aspiring changemakers from all over the world and from all ages joined the online event from 17 to 19 July 2020. They experienced first-hand how transformative it can be to authentically share with and listen to each other.

Despite being online, the conference was highly interactive. It successfully created a safe space and offered plenty of opportunities for participants to get to know each other, reflect on their experiences and share them. Words of gratitude flowed in, as participants left feeling inspired and connected. A Facebook group has been created to offer that community a new venue.

Let’s talk! – Exploring dialogue principles and learning from experienced practitioners

The first day of Tools for Changemakers introduced participants to the tool of dialogue. Experts spoke about their approaches to dialogue and shared their vision for how these can play a significant role in responding to the challenges facing the world.

Dialogue is an enquiry into difference, not a decision-making process.

Simon Keyes

‘Dialogue is a process of thinking about differences,’ said Simon Keyes, Professor of Reconciliation and Peacebuilding at the University of Winchester. He said that dialogue enables us to see how our opinions are shaped by our environment and that it builds trust and relationships. The process is often not easy and requires us to suspend our judgments, to be honest and transparent and to free ourselves from the need to agree or make decisions. ‘The challenge comes from the fact that we are born in different places; it gives us misperceptions of each other,’ said Mohammed Abu-Nimer, professor at the School of International Service of the American University, and senior advisor at KAICIID. Dr Iryna Brunova-Kalisetska, researcher, trainer and dialogue facilitator, drew attention to the fact that dialogue takes time, which we don’t always have in the midst of a conflict.

Let’s listen! – Experiencing a dialogue

For the second day of Tools for Changemakers, participants had the opportunity to experience dialogue themselves. In small groups, they shared their experiences of privilege and discrimination. They learned to express themselves authentically, listen carefully to others and reflect on their experiences, which led to deep connection. ‘Recognizing my privilege has encouraged me to learn more about other peoples’ experiences of oppression and discrimination,’ stated a participant.

Ebony Walden, Matthew Freeman and Rob Corcoran, three dialogue facilitators from the United States, then discussed the role of dialogue in the #BlackLivesMatter context. ‘Often people think that we don’t need to talk, that we need action, but I think that this is a false dichotomy,’ said Matthew Freeman. Dialogue is a crucial step in taking action, as it can help us to get on the same page.

Watch the full discussion here.

Let’s reflect! – Taking inspiration from stories of impact, sense making and looking ahead

For the final session of T4C, two peacemakers shared the impact that dialogue has had on their lives. Angela Starovoytova, a trainer in effective communication from Ukraine, explained how she started her career wanting to ‘share her wisdom with the world’ and for others to adopt her values. She then came to realize that others are entitled to their opinions, even if she disagrees with them. When her father and she kept arguing on their positions regarding Russia’s annexation of Crimea, she decided that their relationship meant more to her than being right and chose the path of dialogue, reuniting the family.

Janine Farah, who is doing a Masters in Peace and Conflict Studies in Australia, told of the courage it had taken for her to enable someone who had suffered deeply to engage in dialogue with a person from the same community as the perpetrators.

Participants had the opportunity to expand these discussions in smaller groups – talking about where they could use dialogue in their own personal and professional lives. Hearing stories from all over the world served as a source of inspiration to participants, bringing them closer together.

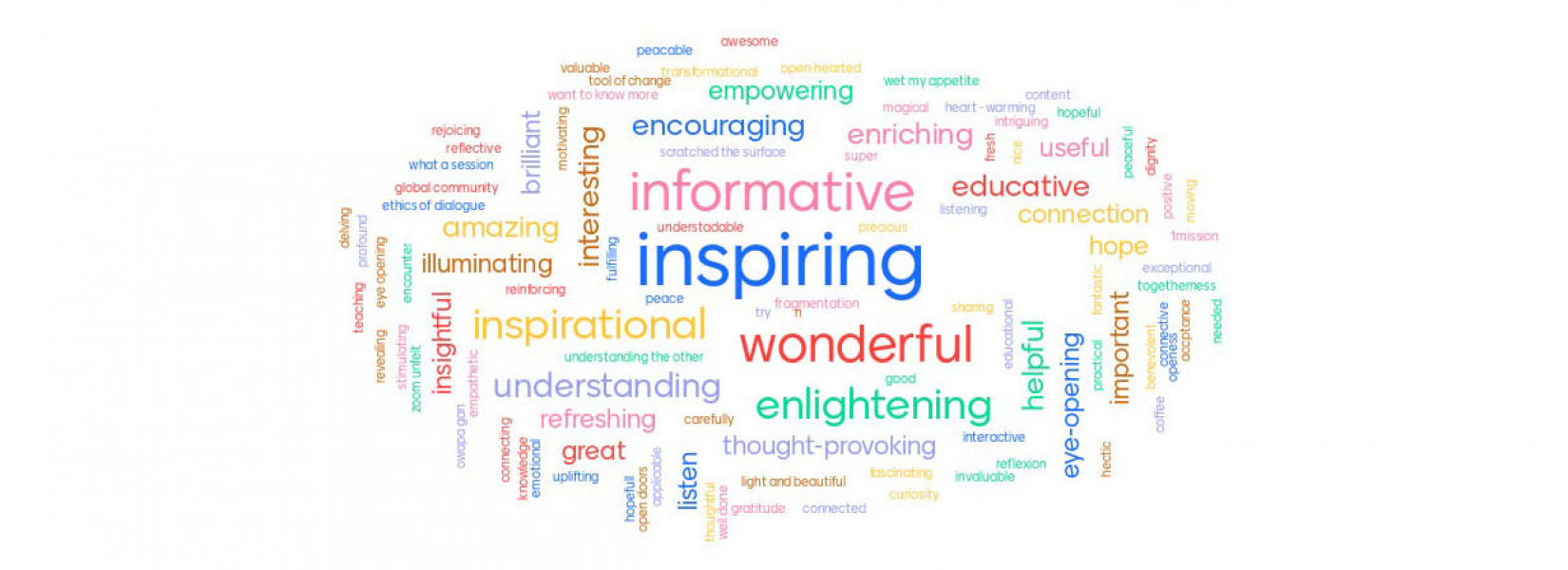

Participants’ words of appreciation showed that they found the experience inspiring and that they enjoyed connecting at a deeper level with others. We look forward to seeing how they will use what they have learnt about dialogue in addressing the challenges faced by their communities.

Thank you to the team for the seamless organization, and to all the participants for their vulnerability and willingness to dialogue, to listen and to share openly. It was a true privilege to be part of this event.

So much gratitude and inspiration! Thanks to the organizers for such a wonderful opportunity to connect with so many change-makers from the world!

Know more about Tools for Changemakers